This article is part of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting

- The number of potentially disruptive technologies in logistics is daunting.

- This makes it difficult for supply chain businesses to know where to look.

- Blockchain, IoT, automation and data science should be first on their list.

Astute business leaders discipline themselves to be on constant lookout for disruptive new technologies.

They foster an internal business culture that is able to evaluate promising technologies through a continuous cycle: Watch > pilot > partner > adopt or discard.

In logistics, as in many other sectors, the number of potentially disruptive innovations is daunting. It includes everything from augmented reality and big data to autonomous vehicles and 3D printing. Even the most agile businesses can’t test or pilot everything, so what’s the right approach?

For companies with goods to move, there are several technologies that bear watching and four that every party in the supply chain should be testing at some level. These four are the BIRD technologies – blockchain, the internet of things (IoT), robotic process automation (RPA) and data science.

The BIRD technologies are inter-related and mutually reinforcing. Blockchain, or distributed ledger technology, establishes trust in data. The IoT provides a vast quantity of relevant data points. RPA improves the accuracy of data. Data science extracts value.

1) Blockchain

Blockchain has its skeptics, including many who believe the technology has already fallen short and might be too inherently problematic. Some skepticism is justified, but it’s premature for blockchain to be written off.

The idea behind blockchain is that all of the information required for completion of a transaction is stored in transparent, shared databases to prevent it from being deleted, tampered with or revised. There is a digital record of every process, task and payment involved. The authorization for any activity required at any stage is identified, validated, stored and shared with the parties who need it.

In ongoing pilots of this technology, shippers, freight forwarders, carriers, ports, insurance companies, banks, lawyers and others are sharing “milestone” information and data about their pieces of an individual shipping transaction. What’s missing today is agreement by all the relevant parties in the supply chain – including regulators – on a set of common industry standards that will govern the use of blockchain.

Absent a consensus on standardization, blockchain offers little. But with a common framework and set of rules, it could make shipping faster, cheaper and more efficient by increasing trust and reducing risk. It would shrink insurance premiums, financing costs and transit times, and eliminate supply chain intermediaries who add cost today but who would become surplus to requirements.

2) The internet of things

As a platform for sharing trusted data, blockchain is ideally suited to the internet of things. IoT devices can be attached to almost anything. As 5G technology evolves and spreads, tiny IoT chips embedded in products will enable businesses to track and monitor shipments of pharmaceuticals, high-tech goods, consumer products, industrial machinery and garments.

That data can be encrypted and shared through the blockchain so that customers and suppliers have a real-time record of the transaction. An IoT-enabled supply chain would be both leaner and less risky. It would allow for true just-in-time production by guaranteeing inventory accuracy and, in turn, reducing working capital requirements.

3) Robotic process automation

Of course, data is no good if it is not accurate. In the supply chain, the leading cause of inaccuracy is human error. Robotic process automation, or RPA, is the artificial intelligence used to allow software to handle many of the steps involved in a shipping transaction by understanding and manipulating data, triggering responses and interacting with other digital systems.

Use of RPA can ensure accuracy in customs declarations, safety certificates, bills of lading and other paperwork. It can reduce reliance on the manually entered data, emails and digital forms that produce errors, create delays and add cost all along the supply chain. RPA frees up workers to be more productive by doing what humans do best: solve problems, react to the unexpected, think creatively and deal with customers.

4) Data science

Thanks to data science, we are in the midst of seismic change in the supply chain. We are getting more data from more sources; it is the right data; and it is accurate. Tools such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and cloud computing enable us to analyze and use that data in powerful new ways.

Rather than using information to sound alarms when there are “exceptions” – problems or anomalies with an individual shipment or in the supply chain – we can use it to prevent them. Data becomes about managing the future, not the present.

The risk, of course, is that only large, well-resourced supply chain players will be able to take advantage of BIRD technologies and other advances that involve harnessing data. That would create a dangerous new digital divide between large and small, haves and have-nots.

Thankfully, data is having a democratizing effect by making the global economy fairer and more inclusive in important ways. Small businesses and emerging markets companies aspiring to go global aren’t piloting blockchain or developing their own RPA applications. But they are already the beneficiaries of new, inexpensive, data-informed tools and platforms underpinned by artificial intelligence and machine learning: online freight booking, instant financing, automated marketing, cheap cloud computing and remote advisory services.

The BIRD technologies generate trust in data, ensuring accuracy and giving users the ability to predict and act. In a data-driven world, they can help businesses of all sizes take flight.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, companies across virtually every goods-based industry have been re-examining their reliance on China, which accounts for roughly 28% of global manufacturing and is a leading source of critical commodities such as rare earth minerals and ingredients for pharmaceutical products.

The China re-think didn’t start with COVID-19

Well before the pandemic, many companies relying on Chinese producers for finished goods and parts were looking to de-risk by finding alternative suppliers in other countries. Why? Geopolitical tensions, trade disputes, and rising costs in China.

Trade tensions and national security concerns have led to a wave of legislation in the United States, where there are more than 60 bills pending in Congress aimed at changing economic relations with China. In addition, U.S. brands and manufacturers comparing China’s labor costs to those in Mexico have seen China’s labor costs rising faster. That has eroded China’s competitiveness and made Mexico more attractive.

Outward migration of production was underway before the pandemic because tariffs imposed by the U.S. and China had increased supply chain costs by up to 10% for as much as 40% of companies sourcing in China, according to Kamala Raman, a senior director analyst at Gartner.

The U.S., Germany, Japan and other countries have expressed strategic concerns about overreliance on China for critical products: 5G telecommunications gear, semiconductors, steel, cranes, electrical power equipment and more. McKinsey identified 180 different products for which one country — most often China — accounts for more than 70% of the global export market. Many of the products are chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Intel recently divested itself of a business in politically sensitive memory chips because the business was heavily dependent on China sales. Samsung and others have cited cost considerations for production moves or asset sales.

The pandemic is turning concern to action

China’s assertive response to the pandemic included lengthy, mandatory lockdowns that froze manufacturing and stranded global cargo shipments for several weeks in the spring of 2020. That caused unprecedented disruption in supply chains and led to shortages of everything from household goods and consumer electronics to industrial components and healthcare products.

The pandemic exposed the fragility of sprawling global supply chains. In one recent survey, one-quarter of businesses sourcing from China indicated plans to transition all or some of their operations to other countries over the next three years. In a Gartner survey, an even higher percentage – 33% — said they intend to pull manufacturing or sourcing out of China in the next two to three years. Sixty-four percent of North American manufacturing and industrial professional said they were likely to bring manufacturing production and sourcing back to North America, in a Thomas Publishing survey.

Look for knock-on effects

Any exodus from China will ripple around the world so expect huge and uneven consequences in other markets. The modest movement to other production and sourcing locations has already led to overheated labor markets and infrastructure bottlenecks in other Asian manufacturing countries.

In some cases, the effort to build supply chain resilience is felt most in far off warehousing and distribution hubs, where companies are adding safety stock or shifting from just-in-time inventory to beefed up “just-in-case” models.

Sourcing diversification is altering the flow of goods into U.S. ports. West Coast ports continue to have a lock on ocean traffic from China and serve as the primary gateway for Chinese goods. But now East Coast ports are receiving higher volumes of containerized ocean goods because, in addition to vessels traversing traditional routes from Europe, the Mediterranean and the Caribbean, they receive cargo from Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and India, which have found it economical to ship via the Indian Ocean and Suez Canal.

In turn, the shift toward the East Coast has driven up industrial real estate prices along the eastern seaboard of the U.S. as companies scramble to set up distribution hubs and e-commerce facilities.

Japan is pushing an ‘Exit China’ strategy

At least 87 Japanese companies have shuttered production in China, moving it back home to Japan or relocating to Southeast Asian countries in response to incentives offered under the Japanese government’s $2 billion Exit China program. Nikkei Asia says Japanese companies “wary of rising labor costs in China and geopolitical factors had already begun reorganizing production prior to the pandemic.”

Japanese investment in Southeast Asian manufacturing – specifically in Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand – was already increasing at twice the rate of investment in China.

It’s not just China

Supply chain risk has been rising for years as costly disruptions become regular occurrences.

McKinsey says weather disasters alone accounted for 40 separate incidents involving damage in excess of $1 billion in 2019. Add the risk from trade disputes, retaliatory tariffs — and a doubling of cyberattacks in a single year at a time when companies are increasing their reliance on digital systems.

Geopolitical risk is unavoidable. Today, 80% of trade involves countries with declining stability scores. “Companies can now expect supply chain disruptions lasting a month or longer to occur every 3.7 years, and the most severe events take a major financial toll,” McKinsey says.

Agility’s Take

Economic trauma caused by COVID-19 will initially shrink the universe of suppliers, not expand it. And new layers of protectionism will leave companies with even fewer choices of supply because they will rob efficient producers — in China and elsewhere — of their competitiveness and make them too expensive.

Uprooting from China is not as easy as it seems. Forty years after it began modernizing, China today holds advantages available nowhere else: unmatched scale; abundant skilled and unskilled labor; sophisticated automation, engineering and sciences; world-class infrastructure and logistics; closely synchronized and integrated supplier networks both in-country and across Asia.

Twenty-five years ago, leaving China meant leaving a low-cost manufacturing center. Today, for some multi-nationals, it would mean giving up on the world’s largest consumer market and an economy growing at twice the rate of the United States before the COVID-19 crisis.

Willy Shih, a Harvard Business School professor, says: “There’s a lot of impatience about this supply chain resilience and reshoring. I like to remind people that it took 20 to 25 years for China to capture the supply chain for many products. And if you want to move the supply chain, we’re not talking about something that will happen in a year, or in a couple of years.”

- When the pandemic dies down, trade protectionism will become the biggest threat to global supply chains.

- This will both drive up prices and make resiliency harder to achieve.

- Accelerated digitalization and uptake of new technologies can help firms find a balance between supply chain resiliency and efficiency.

Seven months into the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses of all kinds are devising ways to protect themselves from future shocks by making their supply chains more resilient. In doing so, they need to guard against the mistake of preparing for the last battle rather than the coming one.

At some point, hopefully soon, the unprecedented global response to COVID-19 will reduce it to a manageable threat that allows us to return to something approximating normalcy in our personal and professional lives.

When that occurs, the greatest immediate and long-term risk to supply chains won’t be a virus. It will be trade protectionism, which was resurgent even before the COVID crisis, and now threatens to choke off the lifeblood we need to speed us toward recovery.

As recently as 2016, trading nations were erecting fresh barriers – subsidies, tariffs, quotas, licensing requirements and other obstacles – at twice the rate they were adopting measures to liberalize trade, according to Global Trade Alert. By 2018, new obstacles outpaced liberalizing steps by three to one. Last year, the ratio was four to one, and the value of global merchandise trade fell by 3%, the first decline since 2015.

Since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, we have seen protectionism intensify. Some emergency moves are clearly temporary. They were put in place by governments to ensure access to the medicines, machines and protective equipment required to contain or treat the virus. In other cases, the aim was to guarantee adequate food supplies for local populations.

Yet these new measures and others have been taken against a backdrop of simmering trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies, the US and China, and a growing chorus of voices in the US, Germany and other countries calling to re-shore, nationalize or find alternative sources for key products and industries such as 5G wireless equipment, semiconductors, steel, electrical power gear, mobile cranes, rare earth minerals and other goods.

The 164-nation World Trade Organization (WTO), normally the body that would quell trade wars and bolster the global consensus for free trade, has been weakened, perhaps fatally, by a loss of faith in its dispute resolution system and the apparent withdrawal of US support.

“In the current alternate universe we’re living in, global trade is collapsing and the WTO and the liberal order itself are in a true existential crisis,” Bloomberg noted in June.

As economies around the world emerge, unevenly, from the pandemic, we can expect demand to begin to strengthen. As it does, trade flows, carrier schedules and inventory levels will start to normalize, and supply and demand will find a new equilibrium.

But normalization won’t mean a return to normal. The World Bank expects a 5.2% contraction in global GDP in 2020. Advanced economies could shrink by as much as 7%, although they are likely to recover faster than economies in emerging or developing countries, the bank says.

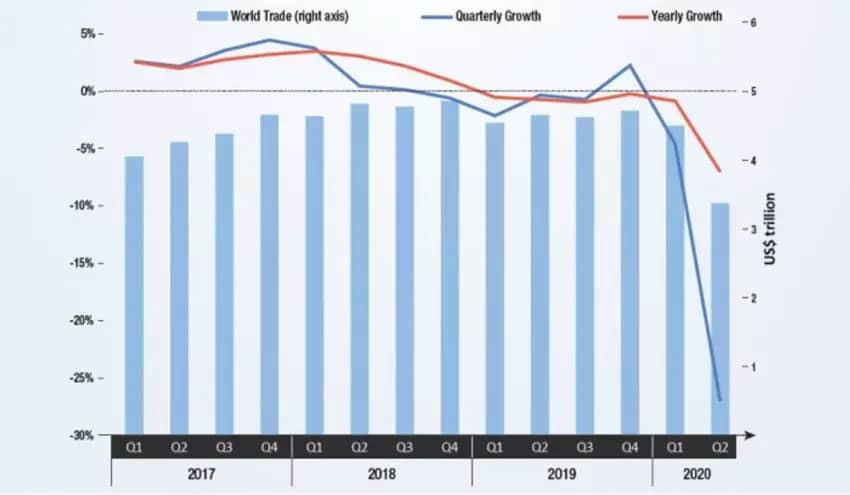

Trade, which has accounted for 54% to 60% of global economic activity in recent years, is set to retreat even further. The WTO forecasts a drop in global trade flows of 13% to 32% in 2020. UNCTAD expects trade to decline by 20%. For context, the largest quarterly decline in trade volume during the 2008 financial crisis was 5%.

Image: UNCTAD

The new wave of protectionism, which includes a sharp rise in the use of international economic sanctions and penalties, will significantly increase the cost of goods at a time when we are experiencing historic levels of joblessness, poverty, and business failures on every continent.

Protectionism is likely to make supply chain resiliency harder to attain, not to mention more costly.

The first step toward resiliency is diversification of sources and suppliers. For many, that means reducing reliance on China, which accounts for 28% of global manufacturing.

Yet the economic trauma caused by COVID-19 will shrink the universe of suppliers, not expand it. And new layers of protectionism will leave companies with even fewer choices of supply because they will rob efficient producers – in China and elsewhere – of their competitiveness and make them too expensive.

Simply uprooting from China is not as easy as it seems. Forty years after it began modernizing, China today holds advantages available nowhere else: unmatched scale; abundant skilled and unskilled labour; sophisticated automation, engineering and sciences; world-class infrastructure and logistics; closely synchronized and integrated supplier networks both in-country and across Asia. Twenty-five years ago, leaving China meant leaving a low-cost manufacturing centre. Today, it would mean giving up on the world’s largest consumer market and an economy growing at twice the rate of the US before the COVID-19 crisis.

Other attempts to build resiliency also defy easy answers. For instance, businesses that see the pandemic as a reason to beef up future inventory through the addition of “safety stock” will probably think differently when the historically low cost of capital begins climbing.

Once the COVID-19 threat recedes, businesses across virtually all industries will have to find a new balance between efficiency and resiliency, because the latter carries a cost. Rather than trying to ‘deglobalize’ or shorten the physical length of far-flung supply chains, they should consider the resiliency offered by accelerated digitalization and deeper integration of technology.

From its earliest days, the pandemic separated digital leaders from laggards. Leaders had tools that gave them accurate visibility into supplier status, orders, shipments and inventory. They could make data-driven decisions quickly because they had trusted supply chain partners – especially freight forwarders and third-party logistics providers (3PLs) – sharing fresh information in near real-time and hunting down available production and shipping capacity. Laggards floundered and continue to flounder.

One obvious lesson from the pandemic is that digital capabilities such as predictive modelling, big data and partner integration are driving business flexibility. When things are relatively stable, those digital capabilities provide a competitive advantage. In times of disruption, they give companies the ability to optimize schedules, ports, modes, vendors and other variables, adjusting on the fly to events that could otherwise prove calamitous, even ruinous.

True resiliency means being ready for any kind of disruption: political, economic, cyber, conflict-based or, yes, pandemic-related. Knowing where to find it is what will separate tomorrow’s leaders from laggards.

Originally published on the World Economic Forum’s Agenda blog

By Biju Kewalram, Chief Digital Officer, Agility GIL

Accurate data and effective supply chain technology are more critical now than ever before. Data-driven decision making is enabling organizations to flex their supply chains to cope with rapid fluctuations in supply, demand and transportation. And as companies and countries attempt to “build back better” from the crisis, lowering carbon emissions has risen up the agenda, and smarter supply chains are an important lever.

Ten years ago, this simply wouldn’t have been possible. Over the last decade, a number of technologies have emerged, with the combined potential to revolutionize the way we move products around the globe.

We’re now moving into the stage of validation and implementation – accelerated by the current crisis – when the whole industry must push past R&D and into the industrial execution of smart systems. This stage will be critical in terms of bringing about actual, sustainable change.

What could the industrialization of these technologies mean for both businesses and consumers, and how can the businesses that haven’t yet implemented them catch up?

The four key technologies driving change in the supply chain are blockchain, the internet of things (IoT), robotic process automation (RPA) and data science (BIRD).

Blockchain generates data trust by enabling all players in a network to share a single (encrypted) database. Anyone with access can track the status and location of a shipment and, more importantly, identify opportunities for efficiencies on a larger scale than has been previously possible.

IoT technology is essential for gathering a vast number of data points. By implementing a system of smart sensors, stakeholders can accurately track sensory data (e.g., location, moisture, temperature, shock), reliably calculating arrival times and proactively responding to disrupted shipments.

RPA improves data accuracy in the chain by substituting human input (and resulting error potential) with software robots that update data within applications by reading them from other applications. This closes the “data confidence gap” when a chain of data updates is required (as in supply chains) to complete the visibility picture.

Data science is the key to unlocking this collective data value and making smarter decisions. Advanced machine learning is continuing to evolve, and AI will one day be used at each stage of the supply chain, although we are some way off this yet. In the meantime, setting up shared databases and making common inferences should be the focus.

What Are The Next Steps?

Now is the time to think about how these technologies can be transformed into deliverable solutions.We’ve spent a long time researching these revolutionary technologies, but only by starting to incorporate them into existing processes can we unlock their full potential.

Organizations at the front of the curve have been analyzing how these exciting digital solutions fit into their businesses, and at our company, we’ve supported a few pilots of certain technologies with clients who are eager to move their companies forward.

So what are the key considerations when piloting new technologies?

Start Small

With a number of technologies waiting to be tested, companies must take an agile, experimental approach. Rather than endeavoring to carry out large-scale trials across the whole organization, businesses should start by implementing the technology in a specific part of the process and gradually scale it up. Working in this way will allow trials to be integrated into day-to-day operations, quickly and effectively gathering firsthand data on multiple technologies.

Consider Your Team

Selecting the right team is vital to running a successful pilot. Ideally, you want a mix of experts who can provide insight on how the technology can be applied to a specific part of the process and the impact this will have on wider business operations. They must also have the analytical skills needed to evaluate the findings and report back to stakeholders. Most importantly, they must be passionate about innovation.

Partnering For Co-Creation

Carrying out individual pilots is one thing, but companies must push the boundaries of cocreation to test these technologies on a larger scale. Any change to the process will have knock-on effects along the supply chain, and the success of many technologies will depend on strong communication. Running pilots with trusted partners of different sizes will allow companies to analyze the adaptability of new technologies. Partners will need to start by agreeing on the problem they are trying to solve and the method they are going to use, as well as how they will measure success and share findings.

Our company’s partnership with electrified trucking company Hyliion is an example of how companies can collaborate to create a more efficient, greener supply chain. We’re helping the company with its long-haul, fully electric powertrain — the HyperTruck ERX. It can achieve a net-negative greenhouse gas emissions footprint using renewable natural gas, and the system’s machine learning algorithm further optimizes energy efficiency, emissions, performance and predictive maintenance schedules.

Gauging Success

Before embarking on a pilot, companies must set out some clear performance indicators and decide on a system for recording results. New technology may show promise for a specific task, but can it be scaled up? What impact would it have on costs, revenue and customer satisfaction? Approaching trials scientifically will help to determine the long-term value these technologies could have in terms of business performance.

Many pilots will inevitably encounter problems, but these experiences are still valuable. A comprehensive debriefing process is necessary to identify whether a failure was due to a weakness in the product or the process and whether these problems could be ironed out through further testing.

Of course, with the logistics industry evolving rapidly, there is no fixed end to the experimentation process. Companies that adopt this systematic approach with an analytical eye and a resilient attitude will thrive in the big data revolution. Organizations must be willing to disrupt their current processes and collaborate because partnerships will be crucial for implementing new technology and making digital supply chain dreams a reality.

This blog first appeared in Forbes

Insights from Frank Clary, VP for Sustainability at Agility

In only a few months, the COVID-19 virus has been responsible for tens of thousands of deaths, with cases in 180 countries. The global pandemic has overwhelmed health systems in highly-developed markets, including Italy and Spain. Informed by the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on more developed countries with strong health systems, the humanitarian community is coming to terms with what could happen in vulnerable countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, already challenged with weaker institutions and networks.

Cascading, systemic risk in vulnerable countries

The combined weakness of core systems – health, telecom, education, food, transport, and others – means vulnerable countries face what are called cascading risks. Upon actualization of one risk, in this case, a health system overwhelmed by a global pandemic, more systemic risks are actualized, leading to the combined collapse of core systems, and potentially complete societal collapse.

In a country with many poor and vulnerable citizens, governments have limited levers that they can pull to help prevent or slow community spread. Many people live day-to-day and risk loss of livelihood if they self-isolate. Many live in precarious, crowded situations where self-isolation is not possible. It will not be possible to control community spread of the virus in communities where individuals must work every day to survive.

A shortage of personal protection equipment (PPE), already an issue in many countries in Europe and North America, precipitously increases the infection rate of first responders. Once infected, first responders cannot conduct tests, contact tracing, or treat patients. With first responders incapacitated, the public health system is considerably weakened, which could increase infection rates and contribute to significant death toll.

Humanitarian supply chains

In a humanitarian emergency, logistics is critically important for saving lives, and typically accounts for 75-80 percent of total spend. This crisis will be no different. The logistics challenge is particularly acute due to the global nature of this crisis, now that more than 50 countries currently restrict the export of medical supplies, including India, where a large proportion of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) used in medicines originate.

Agility is working together with other logistics companies that make up part of the Logistics Emergency Team which supports the Logistics Cluster, led by the United Nations World Food Programme. The companies are creating a dynamic database of information that will be essential to ensure that the 40+ essential items on the WHO’s COVID-19 Disease Commodity Package get to vulnerable countries. The exercise includes data collection and analysis of 4 key factors critical for fast humanitarian response.

- Geographies of risk: which populations are most at risk of systemic failures?

- Export restrictions for countries that are producing essential items

- Import restrictions in vulnerable countries that apply to these essential items

- Capacity constraints for air, ocean and road freight from production countries to vulnerable countries

The sooner test kits, PPE and other essential goods can get to people who need them, the more likely these countries can manage the crisis before it gets out of hand. Agility is also donating warehouse space for storage of humanitarian supplies in Ghana, Malaysia and Dubai.

At the same time, Agility is leveraging its global network, and particularly relationships with suppliers and local governments in emerging markets to get up-to-date information on how the situation is changing. Agility’s COVID-19 Global Shipping Updates are maintained by a network of logistics service providers all over the world, offering information in real time from their countries, as the situation evolves.

A Call to Action: we all can help vulnerable countries respond to COVID-19

For this global crisis, what you do to build resilience in your community, your company, or your supply chain affects the quantity and availability of life-saving products for vulnerable countries. We must keep life-saving cargo moving.

For logistics companies: share information that we can share with humanitarian organizations, particularly in terms of fast-changing export and import restrictions and available capacity

For shippers: collaborate closely with your freight forwarders, carriers, and others – especially for pharmaceutical industry. Sky-high air freight rates and capacity shortages are prompting players to go it alone, just when we need to work together to bring costs down and free up capacity. Collaboration between stakeholders can improve asset utilization, which could help bring costs down and overcome capacity constraints on some critical trade lanes.

For governments: governments need to ensure that exports of humanitarian supplies to vulnerable countries continue, especially to countries unable to limit community spread and to locations where cascading system breakdowns could lead to heavy loss of life and societal collapse. Catastrophe in vulnerable countries will prolong the global crisis for everyone. Particularly for those countries that are ramping up production of PPE and life-saving equipment, it is important to work with humanitarian organizations to consider how to ensure that humanitarian cargo is able to flow freely to vulnerable populations.

For individuals: self-isolate, and reserve PPE and medicines for first-responders who really need them to do things such as contact tracing, testing and treating patients. The faster communities recover, the more expertise, PPE and other life-saving commodities will be available in the global supply chain to reach more vulnerable populations.

The global trade system has a responsibility now to keep cargo moving in order to protect vulnerable populations. #keepcargomoving

Making every mile count

Revolutionizing logistics with digital freight matching

What if you could streamline your business, bolster productivity and slash your environmental impact?

Digital technologies are gaining traction in supply-chain logistics, unleashing a wave of efficiencies and unlocking multiple side benefits. In addition to boosting revenue and slashing operational costs, innovations like digital freight matching are reducing emissions, bolstering productivity and creating a more sustainable industry.

Using transport management software to match a vehicle’s capacity to nearby waiting shipments offers great potential, since lorries and trucks keep the global economy moving. In the US alone, they handle more than 70% of all freight tonnage.

Here are some of the key benefits offered by digital freight matching, which uses online and mobile technology to connect shippers who have cargo to drivers and trucking companies looking for loads:

1. Fewer empty trucks

Empty miles cost money. About 20% of the distance driven by US truckers is non-revenue generating, according to a report by the American Transportation Research Institute. Many industry experts say the actual number could be even higher.

By marrying the cargo to the truck as accurately as possible, applications that offer digital freight matching help eliminate these empty miles, boosting profitability while also lowering emissions and reducing the carbon footprint of the supply chain.

2. Better use of space

In the same way that they help to eradicate empty miles, digital freight tools can also make sure cargo space is being used in the most efficient way. Even experienced shippers can struggle to get the most out of the space on offer in each container and get the best return on investment.

Digital freight matching algorithms quickly calculate the optimal way for loads to be carried, helping drivers ensure they have cargo to carry in both directions before they set off – and all but eliminating the wasteful empty “back-haul.”

One company operating in Saudi Arabia offers a template of how this can work. There, 40% of trucks complete the return leg of their journey completely empty, costing the economy around $5 billion every year, according to the digital platform Homoola, which has financial backing from Agility.

“Knowing how big the inefficiencies were in the traditional way of doing things, we could see the enormous potential of a digital solution that made load-carrying more efficient,” Homoola’s co-founder Ziyad Alhomaid says.

3. Less time waiting

Using the technology in this way also cuts out the time drivers spend sitting idle while waiting for cargo. Connected systems facilitate planning that reduces loading, unloading and clearance logjams at ports and warehouses. In addition to a cost benefit, there’s a huge environmental upside, since an idling engine can produce up to twice as many exhaust emissions as an engine in motion. That releases a range of air pollutants including carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and other particulate matter.

4. More efficient fleets

Using digital freight matching technology allows firms to accurately estimate the numbers of vehicles and drivers required, not only for a given shipment, but also over a longer period. This enables them to right-size their fleets and driver pools, potentially saving significant amounts of money.

5. Less traffic on the roads

Cutting out unnecessary journeys reduces congestion and emissions. Any technology that helps reduce the number of heavy goods vehicles will have an instant environmental impact. In the UK alone, they are estimated to account for around 17% of greenhouse gas emissions from road transport and more than 20% of road transport nitrogen oxide emissions, while making up just 5% of all vehicle miles.

6. Paperless deliveries

Documentation associated with shipping often mounts up. Digital freight matching apps allow this to migrate to the cloud, saving time, money and energy, instantly cutting waste.

“Shipments often come with a lot of paper,” says Homoola’s Alhomaid. “We’re reducing this on the carrier side, as well as for shippers, and working towards a paper-free solution. It saves time, money, energy – and the environment.”

7. More transparent pricing

Technology can also aid price negotiations, letting both sides see a range of different prices, in real time, at the click of a button. Faster, more liquid transactions conducted via an app can be beneficial to both sides.

In 2016, US businesses spent more than $1 billion on logistics, much of which was procured in long-term contracts of more than six months, according to a report by the consultancy firm A. T. Kearney. Signing lengthy commitments is a financial risk for both the shipper and the carrier, whereas a more dynamic market – created by digital freight matching – helps to mitigate these risks because both parties have a better handle on fuel prices, surcharges, tolls, taxes, tariffs, driver’s rates and other costs that they will incur.

Such tools also improve transparency, visibility and comparability of pricing structures, and can be updated in real-time.

8. Stronger safety standards

In the same way that it bolsters pricing transparency, digital freight matching also gives better visibility to the documentation that’s involved in the industry and can help make the safety aspect less opaque. Driver certifications and safety records can be made easily accessible and readable on mobile devices. In time, distributive ledgers could also create instantly shareable records.

At any given time, for example, a shipper can see a truck’s location, have transparency over the associated costs, and gain insights into important points like on-time delivery. Certificates and records are accessible to all who need them, whenever they’re needed.

For Homoola co-founder Asim Alrajhi, this safety aspect goes together with enhancing quality control.

“It’s a fragmented market,” he says. “Things are done on the phone rather than digitally, and often there’s no quality assurance.” While digitalization is still at an early stage, the market in trucking is set to balloon to around $80 billion by 2025, up from around $11 billion currently, according to estimates from market research firm Frost & Sullivan, which also predicts digital freight brokerage will make up the lion’s share of that.

Once such technologies are adopted, they will improve predictability, speed, transparency and sustainability. This will ultimately result in the seamless delivery of any item, anytime, anywhere at a lower economic and environmental cost.

Originally published at the WEF Agenda blog on January 17th, 2019

This article is part of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting

- Small businesses have global potential thanks to e-commerce.

- SMEs active on the internet export more than traditional businesses.

- Heightened economic activity can especially benefit women.

Globalization got a bad rap in part because, by sweeping aside barriers to the movement of capital, labour and goods, it was perceived to have favoured large corporate interests over all others.

With the unfolding e-commerce revolution, however, a fairer and more inclusive balance is reshaping the global business environment to provide more room and opportunity for small businesses, especially those headed by women.

E-commerce: small business accelerator

Today, small businesses – even one-person “social sellers” – can run as global entities thanks to the growing availability of inexpensive digital tools that allow them to source, ship, deliver, pay, collect and virtualize other key aspects of their operations. The fast-developing e-commerce ecosystem, which includes marketplaces, payment gateways and online logistics, is helping to reduce barriers to trade across borders.

Export participation rates for traditional small businesses (those that typically do not sell online) range between 2-28% in most countries. In contrast, 97% of internet-enabled small businesses export, according to the World Trade Organization.

Why is this a big deal? Because firms participating in global value chains see the strongest gains in productivity, income and quality of employment. A report by the World Bank points out that in developing countries like Ethiopia, firms that are part of global value chains are twice as productive as other firms. And in a broad number of emerging markets, companies that take part in global trade are also more likely to employ more women than others with more traditional, male-dominated business models. Female participation in the labour market, in turn, correlates strongly to societal gains in health, education and overall prosperity.

Put simply, e-commerce is creating economic employment opportunities for new sets of players. Amazon claims that the 1 million small businesses selling on its platform have created 900,000 jobs in the process. Alibaba’s Taobao, one of the largest e-commerce platforms in China, has 3,200 “Taobao villages” in rural areas where a significant percentage of the village is engaged in e-commerce transactions. No wonder then, that some non-governmental organizations and think tanks are touting e-commerce as a model for developing rural Africa.

E-commerce: gender accelerator

When it comes to the gender effect of e-commerce, the research is still emerging and much of the data is localized, but early signs are promising.

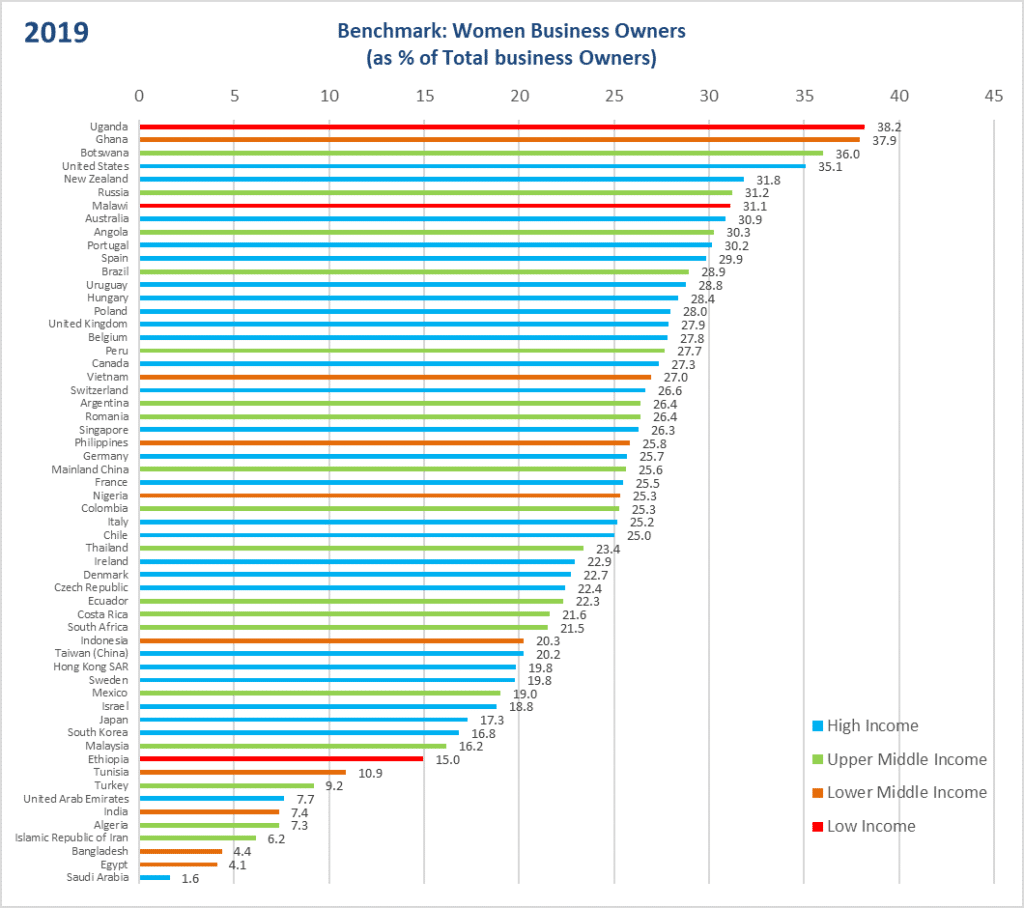

Image: Mastercard

The International Trade Centre (ITC) has found that despite having less access to technology, women use digital platforms to their advantage. The head of the ITC says four out of five small businesses engaged in cross-border e-commerce are women-owned, while just one in five firms engaged in offline trade is headed by women.

Meanwhile, there is more and more evidence to show how e-commerce and digital technology are bringing women to the fore of global trade:

- A McKinsey study on Indonesia’s e-commerce sector found that women involved in online commerce generate more revenue than that contributed by those in traditional commerce.

- Taobao says 50% of its online shops were started by women, whereas only 3.7% of businesses across 67 other industries in China are headed by females, according to the South China Morning Post.

- The World Economic Forum says one in three Middle East start-ups is female-founded. And Cairo-based ExpandCart, one of the region’s most successful e-commerce enablement platforms, says that one-third of small businesses on its platform are owned by women.

Cross-border e-commerce is the fastest-growing segment of international trade, so all of this should come as welcome news for globalization’s critics and fans alike. More importantly, it can help change the two-decade narrative about opportunity, inclusion, fairness and balance in the global economy.

Technology and e-commerce are finally democratizing access to the benefits of global trade, helping globalization live up to its original promise of shared prosperity and growth.

How to integrate new technology into your supply chain

Let’s assume you’re sold on the promise of the digital supply chain. A brave new world awaits if you commit to best use of rapid technological advances. The big question now is how to integrate these innovations into your business.

In our Guide to a Digital Supply Chain, we outlined why an agile approach, based on scalable pilot programs, is essential to evaluating new technologies in a way that is fast, efficient and cost-effective. Here, we will show what that looks like in practice.

Choose your evangelists

Choosing your team is just as important as deciding which technologies to test. The right people will have a mix of the technical knowhow needed to exploit the technology, a broad understanding of how the business operates, and the emotional intelligence to collaborate and communicate effectively with stakeholders.

This is a rare combination – people who possess those traits are to be treasured. More likely, you will create a small team whose members collectively bring these traits. Ideally, this team will represent a cross-section of your business, so that each member approaches the pilot with a different set of questions and priorities.

The job of this team is to evangelize change, so you need personalities excited by change, rather than team members who see change as a threat. If a pilot shows promise, you need people who can spread it wider, scale it up, and convince reluctant colleagues of its benefits.

You will want a mix of subject matter experts, operational personnel and systems integration specialists. Ask yourself what contributions and expertise you will need not just to run a pilot but also to evaluate its success, and then select accordingly. Consider also whether your choices will be able to cope with a fast pace of work in addition to their normal day jobs, and whether they have the interpersonal skills to work well with partners.

Small is beautiful

There are many reasons to keep initial pilots small – starting with the cost. Very few companies can afford unlimited R&D spend, and large-scale trials are expensive. The point of an agile, empirical approach is to try many things to see which work best, so a series of smaller, cheaper tests will tell you a lot more than a complex and expensive pilot.

Small pilots are also easier to integrate into the normal running of your operations, by limiting disruption, and the number of people involved. Change is hard for most people, so the fewer who need to have their daily routines changed for an experiment, the less resistance the pilot team will encounter.

Small pilots can also adapt quickly to different variables. For example, it might become clear very early that the particular IoT device you are testing to track consignments isn’t accepted on your preferred air cargo partner. A small pilot involving one customer’s deliveries could experiment both with changing IoT devices and with trying a different airline with limited ramifications.

Learning by failing

Most successful pilots can start small, then scale up. But you will also learn from the pilots that fail.

Embracing failure may not come naturally, but it is essential. The simple fact is that many, and perhaps most, of the pilots that you launch will run into serious obstacles. The teams will need to decide whether to persevere with the current solution, try again with a new approach, or move on to the next project. Remember the wisdom from the old ballad “The Gambler” by Kenny Rogers: “You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away, know when to run.”

Honest appraisals of why a pilot didn’t work will reveal a great deal about both the technology and the way your own organization is operating. All the knowledge gained should be shared and factored into the design of future pilots, in a constant iteration. Work out in advance how to capture what has been learned. A comprehensive debriefing process is essential.

Failure isn’t final. In any debrief, you should ask yourself whether an unsuccessful pilot is worth trying again and, if so, when – for example, when the technology reaches a certain price point or when a supplier’s or customer’s technical sophistication reaches a certain level.

Picking your partners

In the supply chain, no improvement can be made entirely in isolation. How your suppliers and customers adapt to the changes you make, and vice versa, will determine the success of the chain as a whole.

In Agility’s experience, collaborating on pilots is a win-win. But your partners need to share common goals and agree the following questions: What problem are we trying to solve? How much do we want to invest in finding a solution? Are we prepared to walk away without recrimination if the pilot is not a success? How far are we willing to share what we have learned with the other parties?

If the answers to those questions don’t match, then this might not be the right pilot.

It is also important to run pilots with different types of partners – something that worked well with a local family business might not scale up when applied to a large corporation. Agility collaborates with the full range: from an IoT cold storage pilot with a small firm specializing in one particular cargo in one market, to trials of blockchain with IBM and Maersk.

Don’t rest on your laurels

An experiment doesn’t end when a pilot shows promise. In fact, that is when the hard work begins – working out how to scale the pilot up and what other aspects of your business it can be applied to.

Constant experimentation can be draining, so communication is vital to bringing your workforce with you on your transformation. Strong leaders need to articulate why innovation is necessary, explain the journey, and inspire people to believe that the gain is worth the pain. But they also need to listen to concerns such as increased workload or a fear that their jobs may disappear as a result of the new technology. Anticipate these concerns and have a plan – the hardest part of getting new technology to work is people.

What success looks like

To judge success or failure, you need clear KPIs agreed in advance. A pilot may work in an operational sense, but will you actually extract value from the technology? What are the implications in terms of costs, revenue, customer satisfaction, staffing levels etc? Defining these parameters in advance will stop people getting carried away by a shiny new toy that may not be as cost-effective as it appears.

At Agility, we are constantly running pilots. We evaluate not only the four core technologies that we believe are at the heart of the digital supply chain – blockchain, Internet of Things, Robotic Process Automation, and Data Science [link to each article] – but a watchlist of 16 technologies, ranging from machine learning and the Cloud to 3D printing, virtual reality, autonomous vehicles and drones.

The template for every pilot is the same:

- First define what success will look like, by identifying the key business outcomes we are looking for

- Analyze exactly what we did, and what we found, at each stage of the pilot

- Decide on the next steps, who will be responsible for carrying them out, and the timeframe

- Identify the risks encountered on the way, and what can be done to mitigate them

Using this scientific approach, you can find the technologies that will give you the competitive edge to thrive as the digital supply chain becomes a reality.