How Better Warehouses Increase Trade in Africa

Kuwait-based Agility Logistics Parks customers can log-on to view contracts and make payments.

UK MOD personnel can log-in to the GRMS portal to schedule household relocation shipments.

Kuwait-based Agility Logistics Parks customers can log-on to view contracts and make payments.

UK MOD personnel can log-in to the GRMS portal to schedule household relocation shipments.

This blog was originally published by the World Economic Forum

By Tarek Sultan

CEO, Agility

The global supply chain continues to sputter and break down more than two years into the pandemic. Each day comes news of choked ports, out-of-place shipping containers, record freight rates, and other problems that cause disruption and defy easy answers.

Unless you’re the one waging the day-to-day battle to move cargo for your organization, you should find a moment to take a deep breath. Step back and look at the larger picture because when ports eventually clear and rates come down, the way we manage and think about the supply chain will be very different.

How? Let’s look at the changes in the supply chain brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The supply chain finally has the C-suite’s attention, and chief supply chain officers are its new stars. In October, for the first time, corporate CEOs in a McKinsey survey identified supply chain turmoil as the greatest threat to growth for both their companies and their countries’ economies. Bigger than the COVID-19 pandemic, labor shortages, geopolitical instability, war, and domestic conflict.

At about the same time, Bank of America noted that mentions of “supply chain” in Q3 earnings calls by Fortune 500 companies had risen an astonishing 412% from Q3 2020 and 123% from Q2 2021 earnings calls, when the boardroom focused on the issue was already red hot. Fifty-nine percent of companies say they have adopted new supply-chain risk management practices over the past 12 months, including diversifying to reduce overreliance on China.

“We’re seeing a supply chain that is being tested on a daily basis,” Kraft Heinz CEO Miguel Patricio said recently.

Before the pandemic-driven supply chain disruption, cost reduction and productivity enhancement were driving supply chain process improvements, digitization, and investment. Those drivers remain essential, but the unprecedented chaos triggered by COVID threatened the competitive position — even the survival — of many businesses that found they could no longer meet customer expectations.

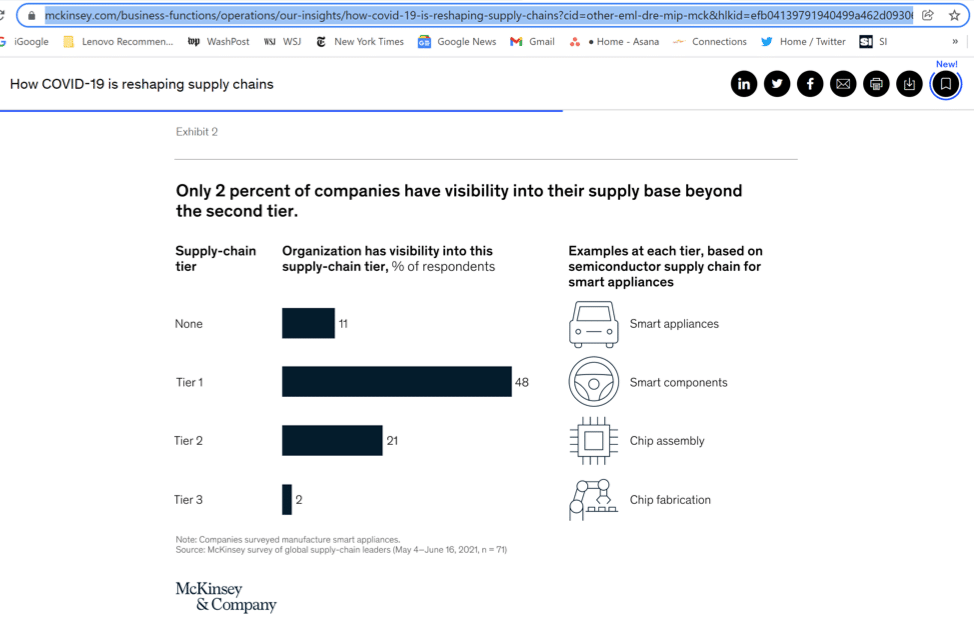

The existential crisis brought on by the pandemic has forced companies to shift the focus of innovation and restructuring efforts to ensure business continuity by building resiliency and flexibility. McKinsey highlighted the vulnerability of manufacturers by showing how few had any visibility into their supplier networks beyond Tier 1 suppliers.

Clorox is one of many companies taking action. It is investing $500 million to upgrade its digital capabilities, citing the need for real-time visibility and better demand planning.

“Supply chain and operations teams must develop new capabilities―and quickly. Playing to a more balanced scorecard will require many changes: reducing the carbon footprint, building greater resilience in the supply chain, creating more transparency, and ensuring accountability,” says Bain & Co. in a new report.

In certain industries, the failure of critical links in the supply chain has led to new alliances and co-development ventures between OEMs and suppliers. Alarmed by the shortage of semiconductors, for instance, Ford and General Motors have formed strategic agreements with chipmakers.

More broadly, there is a recognition that resiliency is impossible unless buyers, suppliers, and other parties along a value chain are willing to share data and collaborate. A new Reuters report, Where’s My Stuff? suggests that businesses could share sensitive, closely held data with partners by creating “cleanrooms” where joint teams can perform analysis without fear that competitive information will leak. Blockchain technology, which enables secure, access-controlled data exchange, also could be valuable in data sharing. It allows data storage and distribution through a decentralized network where there are no owners.

“With the benefits of increasing collaboration through data sharing and visibility into deeper tiers becoming more obvious, addressing mistrust becomes a key objective and will require concerted and directed efforts. … (O)rganizations will need to move closer to their suppliers and build relationships and trust, but they can also use smart approaches to data sharing to make progress,” the Reuters report says.

Bold companies are not waiting for supply lines to untangle themselves. Retailers short on storage space are buying warehouses. Shippers that can’t find containers are making their own. Companies unable to book with ocean carriers are chartering vessels themselves. Those unhappy with their online sales are buying e-commerce fulfillment operators.

Amazon and ocean giants Maersk and CMA CGM are placing orders for aircraft and moving into air freight. Maersk and CMA CGM, in fact, appear to be on a collision course with Amazon and Alibaba in logistics, forwarding, and delivery.

Nimble shippers and manufacturers know they have to keep adjusting. They are using alternative ports, reformulating products, shifting to air freight, boosting in-house trucking, taking advantage of off-peak port hours, and diverting resources from low-margin products to bigger moneymakers.

In its healthcare unit, GE is redesigning products, using dual sources, and expanding factory capacity as it struggles to cope with semiconductor shortages and other supply chain changes and challenges that have caused turmoil in the medical technology industry.

GE and Stanley Tools are among the many companies that have sought to secure goods by shifting production, using forward contracting, turning to contract manufacturers, fast-tracking plant expansion, building new contract manufacturing hubs, using dual-source manufacturing, and nearshoring, or making hard-to-get parts with 3D printing.

Companies know that disappointed customers might not come back. That’s why some consumer product brands are desperate to conceal stockouts and disguise low inventory, even reconfiguring in-store displays and using decoys to hide shortages.

More fundamentally, others are questioning the supply chain models they have worked so hard to make hyper-efficient. Automakers that spent decades fine-tuning and perfecting just-in-time systems have started to break with JIT practices because they don’t work when there are shortages of critical components. Toyota, Volkswagen, Tesla, and others are stockpiling batteries, chips, and other key parts and racing to lock up future deliveries.

“The just-in-time model is designed for supply-chain efficiencies and economies of scale,” said Ashwani Gupta, Nissan Motor Co.’s chief operating officer. “The repercussions of an unprecedented crisis like COVID highlight the fragility of our supply-chain model.”

To ensure they have enough to sell, retailers Nordstrom, PVH, and Gap have tried “pack-and-hold” strategies — over-ordering to prevent stockouts with the gamble that they can stash away unsold inventory and sell it as new next year rather than having to discount deeply.

In other industries built on lean inventories, there is a debate about whether we are seeing a permanent change in strategy – toward larger inventory and more safety stock – or a temporary one necessary because of higher demand.

The Reuters report suggests that more companies are prepared to implement aggressive Continuous Replenishment Programs and automate more of their ordering to avoid getting caught flatfooted without sufficient stocks.

What’s clear is that nearly two years after the world first learned of COVID, the supply chain is still experiencing an unfortunate series of firsts. A historic level of carrier unreliability. Record-high freight rates. Record-low warehouse vacancies. And more.

It will pass. When it does, look for more intelligent options that offer supply chain resilience for both the short and long term.