How Better Warehouses Increase Trade in Africa

Kuwait-based Agility Logistics Parks customers can log-on to view contracts and make payments.

UK MOD personnel can log-in to the GRMS portal to schedule household relocation shipments.

Kuwait-based Agility Logistics Parks customers can log-on to view contracts and make payments.

UK MOD personnel can log-in to the GRMS portal to schedule household relocation shipments.

By Henadi Al-Saleh

Chairperson, Agility

By most measures, women are making steady gains in professional opportunity, pay and status and decision-making power at work. Their progress, while slow and uneven, is reflected in economic empowerment indexes put out by the OECD, World Health Organization, UN agencies and others.

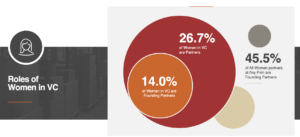

One area where women are advancing little, however, is venture capital (VC). Companies founded solely by women received only 2% of all VC investment in 2022, and only about 15% of all VC ‘cheque-writers’ are women.

In the Middle East, where my company is based, venture capital investment is increasingly seen as a critical component of national economic competitiveness and a source of innovation. The region’s VC funds and corporate VCs are competing with sovereign wealth funds, among the world’s largest and most active VC investors. Yet, startups founded by women in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) received only 1.2% of funding in 2021 and about 2% last year.

The glaring imbalance has sparked lively debate about what’s causing it.

Venture capital is a male-dominated industry and bias, whether conscious or subconscious, is clearly a factor. A Harvard study showed that 70% of VC investors preferred pitches presented by male entrepreneurs over those presented by female entrepreneurs, even though the pitches were identical.

Another analysis has shown that VC investments in enterprises founded or co-founded by women average less than half the amount invested in companies founded by male entrepreneurs.

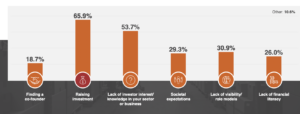

In Inc.’s Women Entrepreneurship Report, 62% of female entrepreneurs said they experienced some form of gender bias during the funding process. Feelings of bias are especially acute among women entrepreneurs in MENA. In a survey of 125 female founders in the region, 58% said MENA investors were less likely to invest in women-led startups than global investors.

The scarcity of female investors – those who sit on fund boards, lead deals, and make investment decisions – is also an issue. However, the authors of a Harvard Business Review article on the VC gender gap caution women founders against focusing solely on pitching to female investors.

“There are still very few female investors, and they tend to be concentrated in funds that focus on earlier-stage investments, where risk is higher and funds invested are smaller. Today, female VCs simply do not control sufficient assets to continue investing in female-led firms as they scale. This means that female founders will ultimately need to attract male investors to grow — and if you’re a woman, our research shows that’s a lot easier to do if you raise at least some capital from men from the start,” they wrote.

Another hard reality is the lack of a pipeline; here I speak from experience. Our corporate VC arm, Agility Ventures, received about 1,000 pitch decks last year. How many came from women-founded or women-led businesses? I can count them on one hand.

The lopsided numbers in MENA are especially perplexing because of the inroads women in the region have made in the educational fields that generate most of the innovation and ideas sought by venture investors. Women now account for 57% of STEM students at MENA universities, according to UNESCO.

Apart from the need to address basic inequity, there are plenty of reasons to tackle the gender chasm in venture capital. The biggest is the chance to unlock economic gains.

Venture funding de-risks the innovation process through bets on promising ideas from smart people who need resources to get their ideas to market. It’s a wellspring of new technology, business growth and economic development, which makes the diversity of entrepreneurship and VC leadership economic imperatives. A widely cited BCG report says global GDP would rise 3% to 6%, boosting the global economy by up to $5 trillion annually if women entrepreneurs received the same investment as male entrepreneurs.

That means networking, mentorship, technical assistance and other support. It means building on the work of investment community participants, such as Women in VC, the world’s largest global community for women in VC to connect and collaborate; AllRaise, an organization dedicated to accelerating the success of women founders and funders; and the Female Founders Fund, an early-stage fund that offers pitching resources and technical help in addition to investing in women-led tech startups.

It also means more non-profit and public-sector programmes, such as empowerME, an initiative aimed at female entrepreneurs in the Middle East; Monsha’at, a Saudi government small business authority with an entrepreneurship programme targeted at women; She Innovates, the global UN Women programme that connects female innovators via app and platform; and Global Invest in Her, a platform for women entrepreneurs seeking funding.

We need to elevate the visibility of female role models who have raised capital and successfully brought products and services to market. Stories of success act as inspiration and provide models for females in business to emulate. Mona Ataya, CEO of Mumzworld, is a good example.

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) highlights one damaging stereotype: that businesses started by women typically aren’t the kind that are right for outside investment because they’re low-tech enterprises in sectors with little potential to scale, trade across borders and go public through stock offerings.

“More attention needs to be given to women who are starting and growing high growth, high innovation and large market businesses. Stereotypes that frame women entrepreneurs as a disadvantaged group feed a false narrative that women lack the same competency as men regarding business leadership,” the GEM team says.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

This blog was originally published by the World Economic Forum.