Originally published at the WEF Agenda blog on January 17th, 2019

This article is part of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting

- Sustainable trade will require the participation of emerging economies.

- Finding the right balance between sustainability and economics is crucial.

- The technology exists; the real barrier is changing existing mindsets.

- Eliminating avoidable emissions is a good starting point.

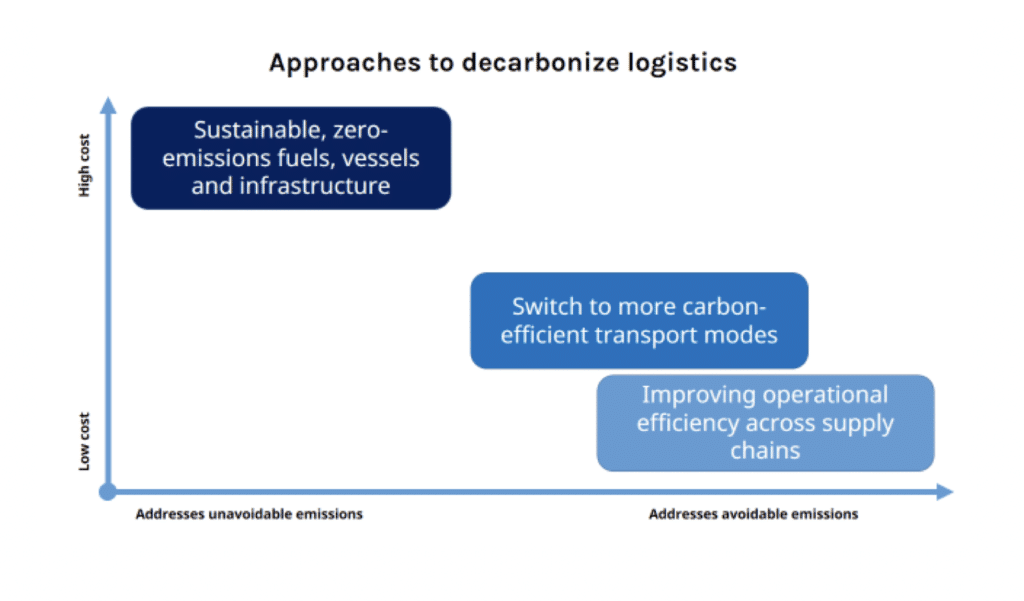

Getting to zero emissions in logistics is a daunting prospect. Developing zero-emissions fuels and vessels is a critical pathway forward, but this approach has its limitations. In a cost-driven industry, a high-cost, high-risk focus on zero-emissions technology may position many players in emerging markets as part of the dirty past – not the clean future. We need a pragmatic approach that balances high-tech practices with practical ones that offer a role for everyone. We can reduce avoidable emissions through more efficient supply chains, but we need to shift mindsets. That’s where we should take immediate steps while continuing the longer journey.

Without the willing participation of emerging market players, a sustainable future for global trade is at risk.

Trade is growing most and fastest in emerging markets, with the growth of import volumes into Asia’s emerging markets as an example. In 2018, developing economies accounted for 64% of seaborne trade. Engaging this majority of actors is essential for the success of the zero-emissions project.

At the same time, we need to balance the environmental with the social and economic aspects of sustainability. If we require investment in new vessels and bunkering infrastructure to participate in global value chains, some actors will simply not comply, and will be left out – and if a port or a country is left out, so are its small and medium-sized firms (SMEs). For SMEs in these markets, accessing global value chains is critical to achieving stable growth and creating jobs. Keep in mind that SMEs contribute over 50% to GDP and account for two-thirds of formal employment in many countries.

Even in mature markets, the largest industry players can’t agree on who should cover the cost of transitioning to a zero-emissions logistics industry.

Logistics is a highly cost-sensitive industry. Just consider that second-generation biofuels are commercially viable, but not available, because no one is yet willing to consistently pay higher costs to ship goods. When given a chance, only a handful of shippers choose the environment over cost. The industry consensus is that a global fuel levy will be necessary to incorporate the social cost of carbon into fuel costs – but action on this has stalled, because oil companies don’t think it’s fair that they shoulder most of the cost burden, even if that cost is ultimately passed on.

Will emerging markets be able to afford the transition to cleaner fuels?

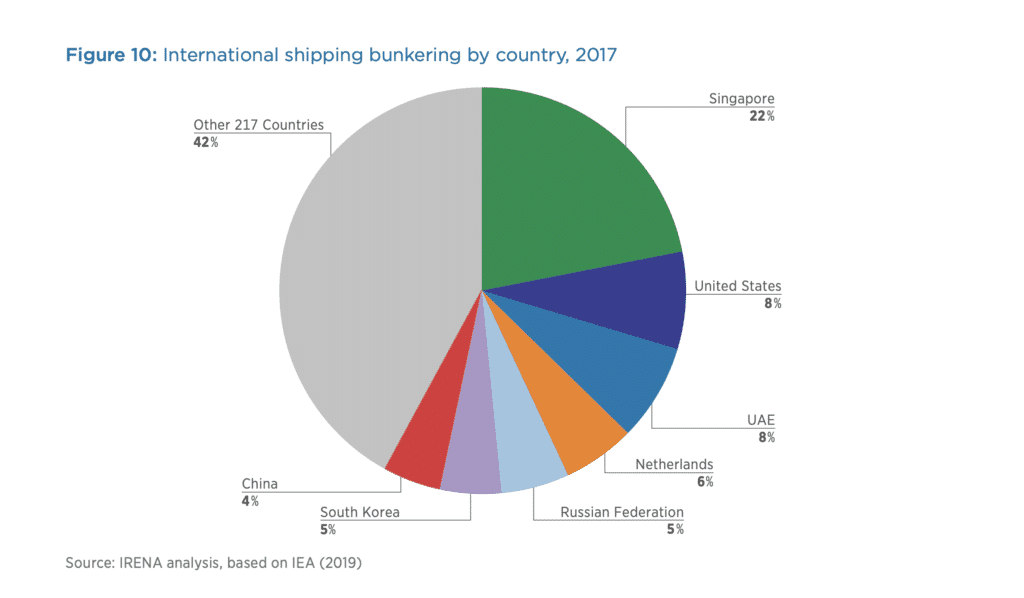

Transitioning to new fuels will be expensive in the short term. Recent research by the Global Maritime Agency – due to be published in late January – estimates that out of up to $1.9 trillion in investments needed to fully decarbonize maritime shipping by 2050, only 13% is for ships. The remaining 87% would be for land-based infrastructure and production facilities for alternative fuels. The International Renewable Energy Agency says “any shift toward a cleaner sector will require important changes to port terminal infrastructure and operational equipment [see chart below], as well as daily operational practices”.

Image: IRENA

Consider coastal African countries, or Viet Nam, where newly-discovered offshore oil resources have the potential to drive considerable growth. How should these countries consider these potential assets in a zero-emissions future? Should they not plan to benefit from their natural resources? Should they, instead, invest in port infrastructure for zero-emissions fuels that they will likely need to import? Is that fair?

The industry should mobilize around practical, system-level approaches to address avoidable emissions across supply chains.

No matter what the fuels of the future will be, it will be useful to reduce the total amount of fuel needed to power global trade. More fuel-efficient transport modes, supply-chain optimization and operational efficiency should be prioritized for their emissions-reducing potential. These solutions are not, and cannot be mode-specific, but must address global logistics as a system.

Image: Authors / IRENA

To address avoidable emissions, data-informed optimization across modes and supply chains deserves more industry attention.

Avoidable emissions are embedded into inefficiencies at every step along the supply chain. It’s tough to measure their contribution to overall transport emissions, but the share could be substantial. Consider that in many markets, sometimes more than 40% of trucks on the road at any given time are moving empty, and a much greater percentage are underutilized.

Beyond individual shippers or supply chains, optimization across the logistics system makes better use of transport assets across a country’s distribution network, or back and forth along a trade lane. On a global scale, the containerization of US agricultural exports addressed the asymmetry of cargo flows between the US and China. Digital freight booking platforms, like Cargo X in Brazil, can drastically improve asset utilization, reducing trips, kilometres, costs and emissions. In the US, when Ocean Spray and Tropicana, two fruit juice competitors, collaborated to enable sharing of empty refrigerated rail boxcars, both parties reduced transport costs, and Ocean Spray’s emissions were reduced by one-third.

The barrier isn’t tech. It’s mindset. How do we shift it?

Logistics is full of myriad actors with high levels of interdependence and competing interests, and this drives down costs. Fierce competition leads to such low prices in road freight that often it is cheaper to send a dedicated truck less than half full than it is to use a small freight carrier. From this baseline, how can industry players work together – in ways that preserve competition – for incremental environmental gains?

First, emissions should be a measured key performance indicator against which supply chain performance is evaluated. For example, some shippers have instituted an internal carbon price. Other sustainability performance rankings can help, both internally and for third-party service providers, but we must be careful to avoid the proliferation of varying questionnaires, and include incentives to improve environmental performance. Immediate exclusion of carriers that can’t meet high environmental standards won’t shift behaviour, and may bankrupt smaller players.

Second, we need to amplify the message about the business case. Logistics services providers can use their visibility across supply chains to identify collaboration opportunities and estimate cost and emissions savings, so shippers can visualize lost value. We all must be retrained and our data systems redesigned to actively look for these opportunities. When collaboration is successful, we need to transparently communicate these stories to clarify what’s possible and set higher environmental aspirations.

Reducing avoidable emissions alone won’t get us to zero. But this approach is open to everyone everywhere, starting now, and it can save fossil fuels in the present, and open the door to zero-carbon fuels in the future.

Brazil is the third-largest trucking market in the world after China and the USA, but has historically struggled with poor road freight infrastructure and a supply-and-demand imbalance between freight and trucks.

CargoX, which has been called the Uber of Brazilian trucking, is using big data, machine learning, and the sharing economy concept to radically overhaul the country’s cargo transportation system.

CargoX has built a marketplace via mobile app that connects over 250,000 truckers with shippers moving goods around Brazil. The app reduces costs for shippers, boosts truck drivers’ income, and increases efficiency.

Since it launched three years ago, CargoX has enjoyed massive success, attracting millions of dollars of investment and swiftly dominating the Brazilian trucking market.

We spoke to founder and CEO Federico Vega about the company’s success, and about how machine learning and big data are transforming trucking.

How is CargoX using data and machine learning to improve Brazilian trucking?

We’ve been compiling and analyzing data since 2013, and more than 60% of truckers in Brazil now connect to our app on a monthly basis.

This level of market penetration provides us with an unrivaled level of data, which makes our real-time updates incredibly accurate. The richness of our data, paired with our technology, is what puts CargoX ahead of any competitor and makes our app so effective.

Our machine learning algorithms can calculate where trucks are likely to be at a certain time, solving the problem of 40% to 60% of trucks in Brazil running empty because they can’t find a load. For example, if a truck is in São Paulo now and will be in Rio de Janeiro in a few days, the algorithm can predict this and can match the truck capacity with freight that needs to be transported.

Machine learning can also help to improve safety and decrease the chances of freight theft, which is quite common in Brazil. Data on freight robberies such as location, type of freight, and time of year are used by the machine learning algorithm to calculate ways of lowering the risk.

By using data and machine learning to improve trucking safety and efficiency, we’re making a positive difference for shippers, truckers, and the wider community.

Why do truckers choose to work with CargoX?

We estimate that truckers can earn around 30% more when they work with CargoX because with other carriers they spend a lot of time traveling empty. Our business model ensures that they are always traveling with a full load, so they make more money per kilometer.

It also provides a more efficient, streamlined process for the truckers. On average, truckers in Brazil have to travel 60 kilometers to find loads. With the CargoX app, you can search for a load nearby, and then secure it and pick it up.

We also solve the problem of truckers going unpaid, by conducting credit checks and background checks on the shippers who use our platform. And once a driver has accepted and delivered a load, they’re paid by CargoX, so we guarantee their payment and take some credit risk on their behalf.

And what about the benefits that CargoX provides for shippers?

Once you open a CargoX account, you can post your freight on a web dashboard and then it gets pushed to drivers via the mobile app, along with the pricing. When a trucker accepts the load, they deliver it and get paid.

Our dashboard enables shippers to track and analyze their loads, which is really useful when shippers are moving hundreds or even thousands of loads every month.

CargoX launched in 2016, and has been very successful in a short period of time. What has been the key to your rapid growth, and what advice would you give to other entrepreneurs?

We were in a good position to grow fast without making as many mistakes as competitors because we had the involvement of highly knowledgeable investors like Agility. CEO Tarek Sultan has been excellent at providing advice and pointing us in the right direction. He’s also been able to make valuable introductions to everyone from financial investors to potential clients, and provided information on things we could do here in Brazil that Agility has done elsewhere in the world.

With a board of directors, advisors and investors who go beyond being sources of capital and who really understand your business, you can get ahead of the competition. We are a trucking company, but we’re also a technology company. One of our investors and directors is Oscar Salazar, co-founder and former CTO of Uber, who has the knowledge needed to run the technology side of the business. And then someone like Tarek has deep knowledge of how to run a logistics business, but also has the entrepreneurial expertise, and knows how to rapidly grow a company. And the involvement of Eddie Leshin, the former CMO of US freight marketplace Coyote Logistics, has been invaluable too.

This depth of knowledge and experience really makes a difference when you’re starting and scaling your business, and also commands more investment, as people can see that you have the involvement of people with experience and you’re more likely to thrive.

As environmental, social, labor and governance imperatives come into sharper focus, the business case (again) for putting sustainability at the core of a company’s strategy.

Growing evidence suggests that businesses everywhere are putting sustainability at the core of their strategic thinking, planning and operations after decades of disconnect between their stated objectives and actions.

Sustainability is finally being embedded into business activity. One reason is that corporate data and academic research have begun to show a return on sustainable initiatives and practices, particularly at companies willing to broaden their definition of Return on Investment and adopt longer time horizons.

Another reason is the growing clamor from a spectrum of stakeholders – consumers, B2B customers, insurers, institutional and individual investors, regulators, community leaders, watchdog groups, employees and job candidates – for companies to demonstrate that they are responsible actors.

The sustainability movement is maturing. Considerations about social and environmental impact are shaping nearly every facet of corporate activity – nowhere more than the supply chain.

“Customers used to think about things in isolation like greening a warehouse, measuring CO2, or getting more visibility into their suppliers,” says Mariam Al-Foudery, Agility Group Chief Marketing Officer, who oversees sustainability and corporate social responsibility.

“Now more customers are looking at the whole supply chain and identifying practices that are connected and mutually reinforcing, things that have impact across business units and operational locations over the long-term.”

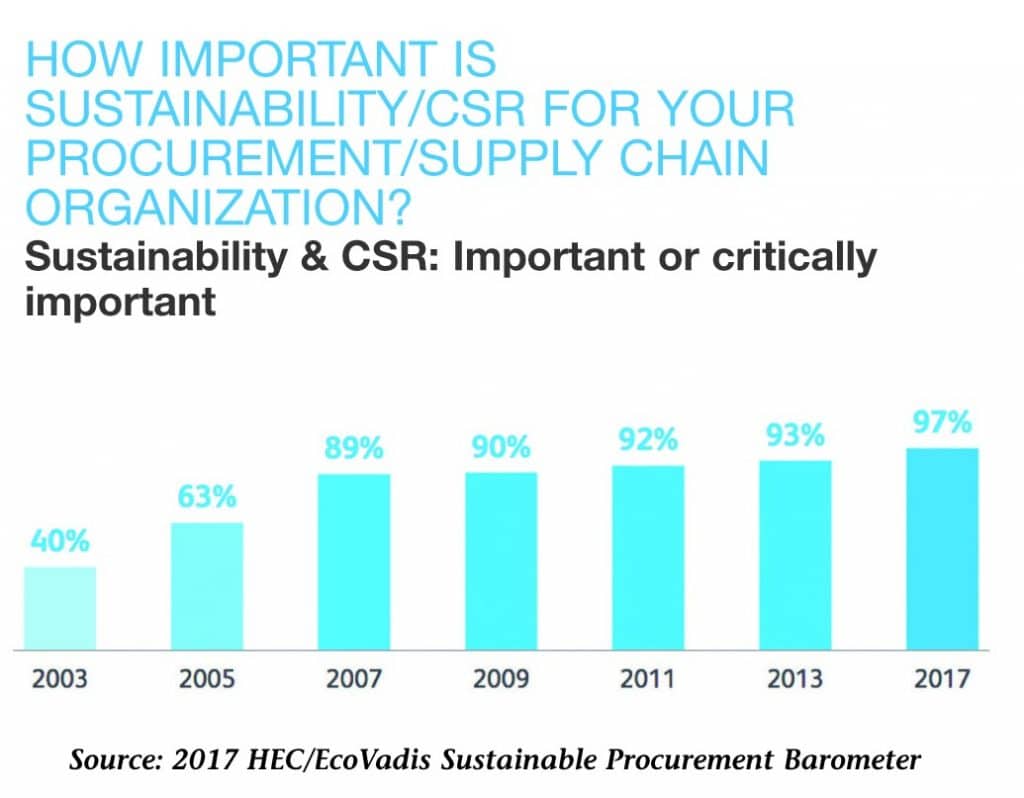

In a 2017 survey by EcoVadis and the HEC Paris business school, 97 percent of procurement officers surveyed listed sustainability as one of their top five priorities. Seventy-five percent of responding companies said they were using sustainability and corporate social responsibility criteria when selecting new suppliers.

What is sustainability?

Sustainable businesses try to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. They focus on good treatment of employees, impact on the environment, impact on local communities, and business relationships with suppliers and customers.

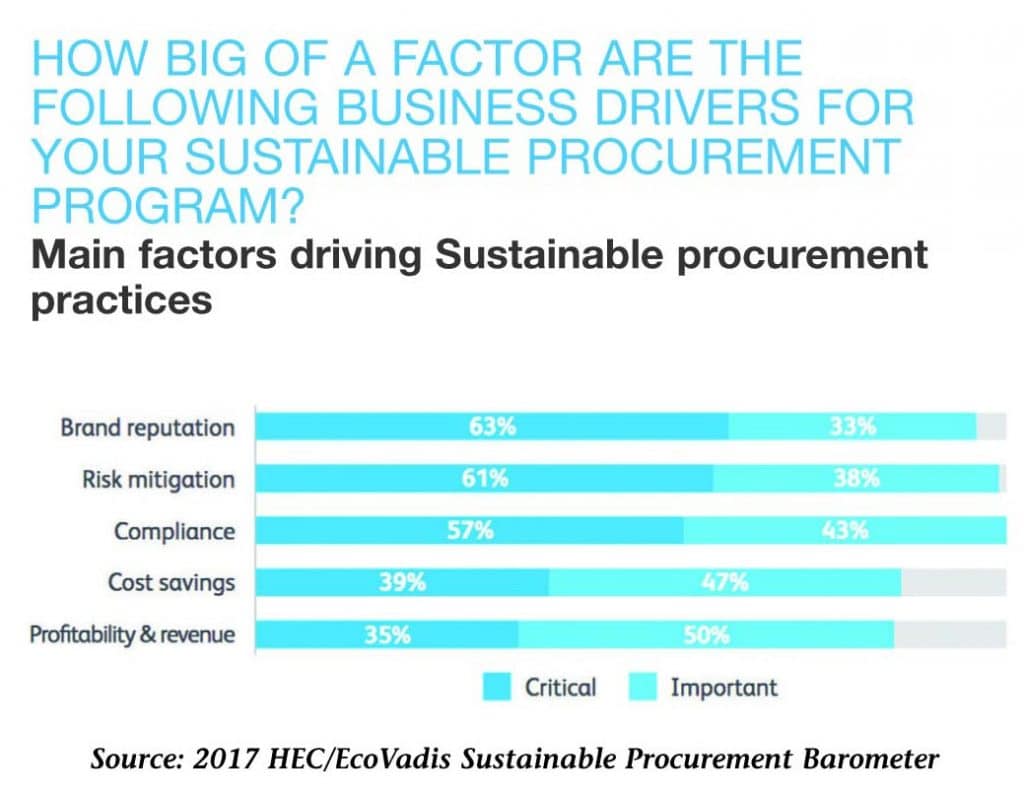

“Sustainable procurement is no longer a nice-to-have – it’s an integral business function responsible for protecting and improving brand reputation, driving revenue and mitigating business risk,” says Pierre-Francois Thaler, co-CEO of EcoVadis, an independent group that provides business sustainability ratings and analysis.

Not everyone is as enthusiastic

Yossi Sheffi, director of the MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics, says sustainability advocates have succeeded in framing the issue as one of “profits versus planet” or “societal good versus corporate evil.” He says that narrative ignores the role of businesses and their supply chains to provide jobs and deliver improved living standards. Sheffi argues that there is a difficult balance to strike and that the real friction is between those demanding environmental stewardship and people who seek jobs and affordable goods.

“Companies are championing their environmental credentials in glossy reports, speeches and media interviews,” Sheffi writes. “At the same time, however, many will admit, off the record, either that they do not believe in the need for this effort, or more commonly, that current initiatives do not meet any reasonable cost-benefit test even if global warming is real and the danger acute.”

Better processes

Others insist there is mounting evidence that sustainability adds real value.

“Embedded sustainability efforts clearly result in a positive impact on business performance,” according to a Harvard Business Review article co-authored by Tensie Whelan, director of the Center for Sustainable Business at New York University’s Stern School of Business. (See Q&A on page 10).

Whelan and her co-authors argue that sustainability delivers significant cost savings from increased operational efficiency and that it drives companies to innovate by creating better processes, new products and equipment, and improved working conditions.

When sustainability is part of corporate DNA, it can “engender enthusiasm from employees, customers, suppliers, communities and investors,” the HBR authors conclude.

The Sustainable Business Council says there is ample research to show that sustainability lowers the cost of capital, results in better operational performance, and has a positive effect on stock price. Sustainability is a major factor in building and protecting corporate value, the SBC says. Consulting firm McKinsey has estimated that the value at stake from sustainability concerns is as high as 70% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

“Forty years ago, the bulk of a company’s value linked directly to its tangible assets,” the SBC says. “Now only about a fifth relates to a company’s financial performance and physical assets. The rest reflects intangible assets like brand, intellectual property, and whether a business has a social license to operate.”

When sustainability is part of corporate DNA, it can “engender enthusiasm from employees, customers, suppliers, communities and investors.”

BY 2035: THE CHANGING ENERGY PICTURE

- Fossil-fueled cars will require 40 percent less fuel to go one mile.

- Energy intensity – the amount of energy required to produce a unit of GDP – will be half what it was in 2013. (Traffic congestion can cost as much as four percent of a country’s GDP.)

- Demand for electricity will grow twice as fast as energy demand for transport.

- Seventy-seven percent of new electrical capacity will come from wind and solar; 13 percent from hydro. (Installed cost of solar has fallen by 70 percent since 2009.)

- The population will have grown by 1.5 billion.

Source: McKinsey Sustainability & Resources Productivity

Agility innovation

Like its customers, Agility is taking aggressive steps to get greener. It is working with carriers to slash CO2 emissions, rethinking warehouse construction and management, piloting use of solar energy in building cooling, and investing in energy-recapture technology for trucks.

Mindful of its social impact, Agility pioneered protections and standards for workers in the Middle East more than a decade ago and has been a leader in sharing best practices and publicly advocating for stronger protections. In 2017, Agility introduced its first stakeholder policy, laying out goals and commitments to protect the environment, safeguard workers rights, improve communities where it operates, and be responsive to the needs and concerns of a variety of different interests.

“The biggest challenge for us and most logistics providers is on the customer side,” Al-Foudery says. “Customers want strategies, tools and technology to help them meet their sustainability goals.” One such tool gives Agility customers the ability to compare and optimize the environmental impact and cost of individual shipments using a nearly infinite variety of shipment types, routes, load sizes and configurations, and other factors.

Zero-impact target

A leading apparel powerhouse approached Agility with the goal of building sustainability into the design and manufacturer of its vast, globally sourced product line. Agility worked with the customer to create an information and standards framework and to build measurement and performance targets into its supply chain.

The apparel customer’s objective is a low/zero-impact, closed-loop supply chain: dramatic cuts in CO2 emissions and energy per unit of manufacture; facilities running 100 percent on renewable energy; 0 percent waste; doubling of supply chain efficiency every 18 months to two years.

“That can be scary, but customers with big, ambitious goals are sometimes the easiest to work with because they’re totally committed. They will take risks in order to become leaders,” Al-Foudery says. “They’re ready to innovate and break from established practices and willing to reward partners who help them achieve their goals.”

Sustainability efforts by consumer products companies and retailers typically get more visibility than those of B2B companies.

Alarmed by oceanic pollution, Nestle, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and Unilever are among those searching for alternatives to plastics from fossil fuel polymers.

Supply chain priority

“The typical consumer company’s supply chain creates far greater social and environmental costs than its own operations, accounting for more than 80 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions and more than 90 percent of the impact on air, land, water, biodiversity, and geological resources,” McKinsey says. “Most of the environmental impact associated with the consumer sector is embedded in supply chains.”

Ethical Corp. estimates that there are about 400 sustainability labels, including Fairtrade, which got its start in 1992 but is being overtaken by alternatives. Sainsbury’s, the UK supermarket chain, is among those that have shifted from the third-party Fairtrade certification, creating its own “Fairly Traded” label.

Unilever and Nike are recognized leaders on environmental and social initiatives. Campbell Soup works with farmers to optimize fertilizer use and improve soil conservation. Walmart gives suppliers incentives for their sustainability performance. Alarmed by oceanic pollution, Nestle, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and Unilever are among those searching for alternatives to plastics from fossil fuel polymers. Target, Keurig and others are pushing suppliers of industrial plastic items such as crates and trash bins to use more “post-consumer” material.

Worker rights

The safeguarding of worker rights and improvement in working conditions is often the most difficult issue on the sustainability agenda.

Five years after the Rana Plaza factory collapse that killed 1,100 garment industry workers in Bangladesh, independent assessments report improvement in factory safety and monitoring by the government and local companies. But two organizations representing western brands and retailers recently said local authorities still aren’t prepared to assume responsibility for policing safety standards.

Worker rights can be a contentious issue even for global leaders such as Nike, which developed many of the best practices now used by apparel brands and manufacturers. Nike has voiced objections to advocacy groups positioning themselves as third-party auditors, arguing that there is a conflict of interest for groups that are both campaigning and auditing. For their part, advocacy groups say many audits go too easy on brands and manufacturers.

But failure to tackle environmental and social risks can have punishing consequences. Apparel companies that contracted with Rana Plaza garment makers fell from lists of most-reputable companies in the aftermath of the tragedy. Aussie GrainCorp reported that drought cut its grain deliveries by 23 percent and led to a 64 percent drop in 2014 profits. Unilever estimated that it loses 300 million euros a year as worsening water scarcity and declining agricultural productivity contribute to higher food costs.

It is through experimentation and innovation, not spreadsheet projections, that viable sustainable business models emerge.

The business case for sustainability

Forum for the Future, an international sustainability nonprofit, says the companies set to benefit are those that can “capture the less tangible benefits as well as direct financial savings, for example, the clear reputational benefits of the initiative.”

The business-case numbers “are much ‘softer’ than decision-makers are used to,” the Forum says. As a result, “companies get stuck in a vicious cycle: they want a business case before giving permission to go-ahead with a project, but the information to build a business case can only be generated from the experience of going ahead.”

George Mason University professor Gregory Unruh says it’s time to look at the business case for sustainability a bit differently. “Multi-dimensional sustainability value is just hard to fit into a discounted cashflow analysis,” he writes.

Despite being hard to measure, Unruh writes, “investors are now realizing that sustainability performance feeds the long-term bottom line. And that’s causing managers to question traditional business thinking. So instead of spending time building a perfect business case, many are pursuing business model innovation experimentation, taking a page from Silicon Valley start-ups. It is through experimentation and innovation, not spreadsheet projections, that viable sustainable business models emerge.”

A look at the Gulf region where solar energy has been a tough sell in the face of cheap electricity subsidized by governments with abundant oil and natural gas.

Standard photo-voltaic solar systems have proved vulnerable to searing desert heat and frequent sandstorms. System installation costs have been too high, and paybacks too long and uncertain.

Today however, after a prolonged period of low oil and gas prices, Gulf countries are reducing or eliminating subsidies to consumers and commercial customers. Ambitious national economic diversification plans call for energy conservation and mandate cuts in consumption, along with blueprints for development of green communities and cities deriving most if not all of their energy needs from renewable sources.

Technology advance

The introduction of revolutionary new high-vacuum solar thermal systems – a robust and highly efficient means for generating thermal energy – is proving to be a game-changer. Solar thermal is ideal for the intense Gulf heat and one particular type of high-vacuum technology is capable of operating with minimal output losses even after severe sandstorms.

Air conditioning for Agility’s corporate headquarters in Sulaibiya, Kuwait is provided by a solar-driven cooling system that ran automatically and unattended for over 365 days with 98 percent reliability. In addition to delivering consistent and reliable energy output, the system, powered by a solar field manufactured by TVP Solar, SA of Switzerland, contributed 43 percent of the points necessary for the new building’s LEED Sliver certification. Highest output is achieved from 10am to 3pm each day in a climate where outside temperatures can reach 54 degrees centigrade (129°F), supplying 70 percent of the facility’s required cooling load.

Investment

Agility has invested in TVP Solar and is introducing the technology to commercial and industrial customers, says Steve Lubrano, CEO of Alternative Energy Solutions, an Agility affiliate.

Lubrano says the solar-thermal system and its components are relatively maintenance-free and are integrated into existing buildings. Despite blowing sand and dust, users need not worry about precision cleaning of panels because of their remarkable efficiency and ability to capture both direct and diffuse light.

The technology is becoming even more attractive as electricity costs rise and solar-thermal payback periods fall from a previous six to nine years to a more feasible three to five years.

Interest is expected to intensify as Gulf governments look to expand and “green” their energy production capabilities to ensure supplies for new industry and for energy-intensive uses such as water desalination.

“Oil-dependent countries have come to realize that if they’re burning it, they can’t sell it. That might not be a problem today, but it will be down the road,” Lubrano says. “So we’re seeing a sea change. Kuwait, UAE, Saudi Arabia and others have implemented energy mandates and have made plans for cities powered almost exclusively by renewable sources. We’ve gone from a lack of interest to, wow, ‘You mean you can provide energy and reduce electricity demand at the same time?’ ”

When implemented at scale, Lubrano says, “Yes, we can.”

Oil-dependent countries have come to realize that if they’re burning it, they can’t sell it. That might not be a problem today, but it will be down the road.

Best practices for sustainability in supply chain also mean tough questions for companies. Agility’s Mariam Al-Foudery lays out some key areas for consideration.

Best practices for sustainability are evolving as rapidly as any aspect of business, driven by new technology and an urgency for companies to demonstrate that they are effective environmental stewards and positive contributors to society.

Here are some key areas where logistics providers and their customers need to focus.

-

Traceability

Do you have upstream supplier visibility? Do you do supplier assessments and benchmarking? -

Labor

If migrant workers are in your employee mix, are you certain that they aren’t being exploited by labor brokers and unscrupulous recruiters, a problem that is particularly problematic for companies that hire from India, Nepal and East Africa?

Have you continued to focus on living and working conditions? Are you confident you have transparency into subcontractors? Have you created effective worker-grievance mechanisms? Are you educating and training workers on their rights? -

Energy

When you expand your truck fleet, are you adding CNG fueling stations and LNG vehicles? -

Packaging

If you are a consumer company, what about dimensional weight pricing? -

Warehousing

Have you looked at automation and cleantech in cargo handling and warehousing? -

Port selection

Are you routing shipments through “green terminals” that manage and contain possible pollutants and police for invasive species? -

Logistics digitization

Agility is among those using advanced algorithms to evaluate multiple scenarios and create optimal plans with the least environmental impact. Multi-echelon Inventory Optimization is another tool available. -

Data and measurement

Are you capturing, sharing and analyzing data with your logistics provider so you can get real-time feedback to optimize operations and make sure you are conserving, recycling, recovering and reusing as much as you can?

A sustainable vegetable garden in the arid demilitarized zone between Sudan and South Sudan brings relief to workers supporting the peacekeeping mission.

At the remote end of the supply chain, Agility’s GCC Services team of 105 expats and local staff supplies international peacekeepers with food and bottled water that is trucked hundreds of miles from the Port of Sudan to the mission in Abyei, Sudan.

Desperate for a quiet respite and something fresh to eat in a conflict zone, GCC personnel built a composting operation to turn kitchen waste into fertilizer and began bringing seeds back to Abyei when they returned from leave. The result is a lush, pesticide-free garden of herbs, vegetables and fruit.

The Abyei kitchen garden has yielded large quantities of nutritious beans, peas, jackfruit, guava, lemons, bananas, cassava, tomatoes, aubergines, cucumber, okra, watermelon, lettuce, coriander and other produce.

“This sounds like a small thing, but it’s not. Conditions in Abyei are austere, and the workdays are very long,” says Rashad Sinokrot, CEO of GCC Services. “The kitchen garden has created shade and greenery where there isn’t much of either. It’s been a stress reliever and teambuilder, and demonstrated that you can do something sustainable in a very harsh environment.”

The United Nations calls modern slavery – human trafficking, child labor and debt labor – the world’s second-largest criminal industry.

Efforts to monitor and crack down on modern slavery have forced companies worldwide to scrutinize their supply chains.

The most widely known attempt to mandate corporate transparency is the United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act of 2015. As a result of annual reporting by companies, the UK government estimates that at least 13,000 people are victims of forced labor, sexual exploitation or domestic servitude, Thomson Reuters reported recently. More than 5,000 potential victims were referred to UK authorities last year, a record number.

Worldwide, the Council on Foreign Relations estimates there are 40.3 million victims of enslaved labor and that one in four victims is a child. The Modern Slavery Act “has done a lot to raise awareness,” Kate Roberts, head of office at the Human Trafficking Foundation, told Thomson Reuters. “Unfortunately, in practice, we’re still waiting to really see many tangible outcomes from it yet.” The Business and Human Rights Resources Centre notes similar “lagging” efforts in FTSE 100 firms with operations in the UK.

How it works

-

Who reports:

Any organization that conducts business in the UK and has an annual profit of £36 million ($50.1 million) must issue a statement within six months of the financial year’s end detailing how it has audited the supply chain and operations for slavery risks and violations.

-

What to report:

There is no template for the report, but it should be concise, written in English, approved by the organization’s board of directors; signed by the director or equivalent, and published on the organization’s public website, linked to from the homepage. UK subsidiaries, UK branches and global organizations with a significant presence in the UK (including offices, assets, clients and trade relationships) are also beholden to this obligation, a Harvard Law School forum on corporate governance and financial regulation suggests.

-

How often to report:

Annually. Each year’s report should show improvement in corporate transparency – meaning that the organization’s workforce is being educated about modern slavery, policies are being created to prevent slavery or protect those who fall within a risk category (seasonal workers, unskilled laborers and those who work in potentially dangerous environments), and resources such as budget and staff are being allocated to address risks within the organization.

-

Failing to report:

The consequences include an injunction from courts to comply, and possibly a fine.

-

Accountability:

The Modern Slavery Registry (modernslaveryregistry.org) keeps track of all published reports across 27 sectors, ranging from capital goods and consumer services to pharmaceuticals. This website also measures organizations’ compliance with the Modern Slavery Act; as of April 2018, only 19 percent met all minimum requirements.

Businesses are greening their warehouses to lower costs and reduce resource in pursuit of zero-net energy (ZNE) even without the pressure of government regulations.

A 2010 mandate in Europe is pushing companies there to achieve ZNE status for commercial buildings by 2020. To be ZNE, buildings must create onsite energy equivalent to the amount of energy they use. In the Middle East, Asia and Africa, where most of Agility’s warehouses are located, ZNE is still a distant objective. Michel Saab, CEO of Agility Logistics Parks, Operations, says the two most expensive warehousing costs are lighting and air conditioning. Ed Klimek of KSS Architects notes that lighting accounts for nearly 30 percent of the energy use within a distribution center.

Finding a sustainable solution for lighting is easier than solving the problem of exorbitant airconditioning costs. “Most of what can be done is already done at Agility,” Saab says. Skylights that provide natural light are an option for warehouses where temperature-controlled goods aren’t stored. At Agility warehouses, LED lights have replaced typical incandescent and fluorescent bulbs. Energy Star estimates that LED lights are 90 percent more efficient than incandescent lights. Another cost-savings measure is to connect lighting to a motion-sensor system that will turn off lights automatically in unoccupied spaces.

Agility has the capability to operate a similar system by customer request, but there are technical constraints in spaces where light fixtures are embedded in 14- to 16-meter high ceilings. Air conditioning is expensive and drains a lot of energy, especially in the Middle East. “Agility is looking for new air conditioning solutions, and it is a priority because of the extreme heat,” Saab says. It’s too early to say there’s a direct, viable alternative to conventional air conditioning, but Agility is finding green workarounds. Warehouses can be oriented to avoid direct sunlight and maintain low thermal heating, and UV-blocking skylights can be installed to reduce heat up to 85 percent. What’s more, water-cooled chillers can be used instead of air-cooled chillers to reduce electric demand. Simply defined, a “sustainable warehouse” is one that makes little impact on the surrounding environment (including land, water sources and wildlife), draws modestly from external power sources and is a comfortable environment for employees to work in. Though typically located on the fringes of communities – closer to air and seaports or major trucking thoroughfares – warehouses can have a major effect on a community.

They generate jobs, but they can also draw significantly from the power grid and contribute to pollution. Adopting sustainable practices within a warehouse not only benefits the community, but also makes the warehouse less expensive to operate over time. A warehouse generating its own power is also more stable; it’s not subject to power grid interruptions that compromise security systems or cold storage systems for special products. For its part, Agility is making strides toward ZNE.

“We’re working toward putting photovoltaic panels on warehouse roofs to generate our own power and electricity,” Saab says. Any effort toward environmental sustainability must be sustainable for the business as well, and that’s the current challenge. “We measure our energy consumption to pay the bills,” Saab says. But in the future, Agility can analyze those measurements to identify areas where energy use could be reduced – or even produced on warehouse premises.